From "Hedge Funds Are for Suckers" in Bloomberg Businessweek:

One chief investment officer at a $5 billion institution breaks down the typical hedge fund life cycle into four evolutionary stages. During the early period, when a fund is starting out, its managers are hungry, motivated, and often humble enough to know what they don’t know. This tends to be the best time to put money in, but also the hardest, as the funds tend to be very small. Stage two occurs once the fund has achieved some success, when those making the decisions have gained some confidence ...

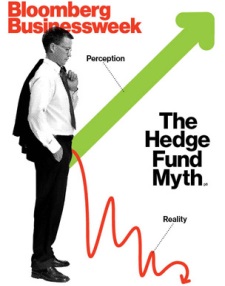

Then comes stage three — the sort of plateau before the fall — when the fund gets “hot” and suddenly has to beat back investors, who tend to be drawn to flashy success stories like lightning bugs to an electric fence. Stage four occurs when the fund manager’s name is spotted as a bidder for baseball teams or buyer of zillion-dollar Hamptons mansions. Most funds stop generating the returns they once did by this stage, as the manager becomes overconfident in his abilities and the fund too large to make anything that could be described as a nimble investing move.

'The bigger a fund gets, the more difficult it gets to maintain strong performance,' says Jim Kyung-Soo Liew, assistant professor in finance at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. 'That’s just because the number of opportunities is limited in terms of putting that much money to work.'

In my career, I've worked with DRTV companies in all different stages of their life cycle. Change a few words, and the above is a fairly accurate description of those stages. Companies start out "hungry, motivated, and often humble enough to know what they don't know" -- and can never really know (i.e. what the consumer will buy). Then they get hot, and their managers gain confidence. This is when the owners tend to buy exotic cars, giant homes and prime office space.

Finally, the companies become "overconfident in ... [their] abilities" and "too large to make anything that could be described as nimble" moves. This is the phase when companies either start to crumble under the weight of their overhead or get smart and begin to import projects from ... smaller, nimbler companies in the early stages of their life cycle.

The core problem is what Prof. Kyung-Soo Liew describes: "[T]he number of opportunities is limited in terms of putting that much money to work." Or as I have put it: This business doesn't scale linearly. There are only so many hits, and just because a company went 1 for 5 when it was small and testing 20 spots per year, that doesn't mean it can go 1 for 5 when it's big and testing 100 spots per year. Four hits per year may be the maximum, or near maximum, for any one company in a given year -- regardless of the company's size or wealth.

What do you think? Post a comment.